second part

This famous temple is the most complete and ancient monument in Rome. It is formed by a round dome preceeded by a pronaus and a large portico with columns. it is one century and more that the reciprocal relation between these two parts has been discussed; some very recent studies have made the inscription clear. It" may be resumed as follows. The temple was dedicated to the seven gods of the planet (whence its name) by Marcus Agrippa, one of Agrippa's nephews. Quite rebuilt by Adrian it is just as we admire it to -day. Adrian made the founder's name repeated on the gable. The three parts, the portico, the antiportico and the rotunda were built in different times, but one after the other. Septimius Severo and Caracalla as it results from an inscription, provided to the rebuilding of the decorative part and to a new paving. In 609 it was transformed into a Christian church (S. Maria ad Martires) by pope Bonifacius IV. The Emperor Constant II (663) took from the roof the tiles of golden bronze which were afterwards substituted by Gregory III (735) with others in lead. In Middle Ages it was suffocated by shabby constructions, then taken off by Eugenius IV in 1435. The last transformation was due to Bernini, who built the two little peels, taken off afterwards in 1893. The level of the square was anciently much lower. A staircase whose remains still exist led to the temple. The grandiose portico is in 16 columns on three naves; 14 columns are in grey and pink granite, the three ones on the left were replaced by Urban VIII and Alexander VII, whose armorial-bearings are on the head-bands.

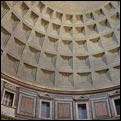

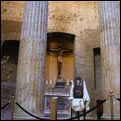

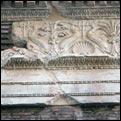

The roof, with wooden beams, was rebuilt by Urban VIII who took off the ancient bronze linings. On the fore part of the pronaus there are two large niches which are said to have contained the colossal statues of Agrippa and Augustus. The door lined in bronze is still the ancient one. The inside has a majestic dome leaning on an attic; the height of the dome, equal to its diameter, is 43,40 metres. It is a perfect emisphere. Of the 7 niches, four are rectangular and three 'half circular. They are faced two Corinthian columns. Between the niches there are 8 stationl, afterwards transformed into altars with columns in porphiry and granite; above there is an entablature and an high attic. The panelled vault ends in a large central ho1e having a diameter of 8,92 metres. It gives light to the whole building and puts into mystic communication the divinities with the sky; it is framed with bronze. In the first niche on the right there is a beautiful Annunciation, a fresco attributed to Melozzo da Forlio In the next one there is the grave ofVictor Emanuel II (1878) by Architect Manfredi. On the high altar there is the image of.the Virgin who gave the Christian name to the temple. In the posterior part of the Pantheon there are some remains of the Baths of Agrippa, a large apse and an entablature richly carved with marine ornaments

Soon after the high altar in the rectangular niche there is the marble memorial of Cardinal Consalvi. Between the fifth and sixth niche there is the grave of Raphael Sanzio, on the fore part of the sarcophagus we read the famous inscription of Bembo: "Ille hic est Raphael, timuit qui sospite vinci rerum magna parens et moriente mori" (Here is that Raphael by whom while he lived the great mother of things feared to be won, and when he died she too feared to die). On the altar there is the Madonna hy Lonrenzetto (Madonna del Sasso). A tombstone above it is the funerial memorial of painter Hannihal Carracci and on the right of the altar the·memorial of Mary Dovizi da Bibbiena, the fiancé of Raphael. There follows the grave of Humbert I, king of Italy (1900), by G. Sacconi, and of queen Margaret. On the left of the following altar and in the seven niche there are tomb-stones and graves of very great artists: Balthasar Peruzzi, Thaddeus Zuccari, Flaminius Vacca.

This work was long attributed to Agrippa, and was claimed by some to have been originally a portion of his baths, but the best modern scholars unite in believing that it was never anything but a temple, and in awarding the honour of its construction to the great builder, Hadrian, who probably erected it to take the place of an older structure of Agrippa's. Its name indicates its dedication to the worship of " all the gods " (jrdv Deiov). It has given rise to much discussion among archaeologists, and has been called the Sphinx of the Campus Martius. Without going into a further discussion of its date and purpose, let us enter through the grove of columns which support the portico. The great dome is above us with its central eye, through which the sun looks down by day and the stars by night. Across the dome it is nearly 150 feet; and some thirty feet across this circular window toward the sky. The Pantheon was a new conception in architecture. It was the first dome, the parent of the Santa Sofia at Constantinople, of the Duomo at Florence, of the great St. Peter's, which now looks down upon it from across the Tiber, of the Pantheon at Paris, of St. Paul's at London, of the Capitol at Washington, and of numberless court-houses and city halls from Russia to Brazil. But as it was the first, so also is it the greatest. Not like modern domes, a shell of iron girders covered with slate or tiles, but built of solid masonry, and depending for its support wholly upon the principle of the arch, — an experiment in architecture, but an experiment so successful ' that it has withstood the attacks of invading foes, of iconoclastic popes, and of consuming time, and remains intact to-day, when almost every other building contemporary with it is in ruins. The Pantheon has had a history. It is the oldest building in the world which has seen continuous use, and its usefulness has extended over a period of nearly two thousand years. When Christianity took the place of paganism at Rome, it was transferred from the service of " all the gods " to that of " all the saints," and filled with the bones of the martyrs from the catacombs. This reconsecration was the occasion of adding a new festival, " All Saints' Day," to the calendar of the Roman Catholic Church. Without, the walls of the Pantheon werf. covered with marble, and its roof was bright with gilded tiles. Within, it was ceiled with plates of bronze, and faced with marble slabs of varied colours. Beautiful caryatids supported the architrave, and a mosaic floor reflected the sunlight which streamed down through the opening above. But it has been stripped of all this decoration. One of the Barberini popes converted the bronze ceiling into the canopy that stands in the centre of St. Peter's, and what was left was moulded into a few score cannons, with which to shoot down heretics and heathen. His sacrilege is piously recorded in the following inscription, which we may still read upon the wall : "Urban VIII, that the useless and almost forgotten decorations might become ornaments of the apostles' tomb in the Vatican temple and engines of public safety in the fortress of S. Angelo, moulded the ancient relics of the bronze roof into columns and cannons, in the twelfth year of his pontificate." This suggests the witticism of Pasquino, who, mourning over the loss of these and other ancient relics, suggested that the destruction which had been left undone by the barbarians had been accomplished by the Barberini. ("'Quod non fecerunt barbari, fecerunt Barberini.")

Whitewash now covers the walls and ceiling of the Pantheon, and the only suggestion of the old magnificence is in the columns of beautiful yellow marble with white marble bases and capitals. A few bits of porphyry and verde antique cling also to the walls, making more pitiful the contrast with the lime, the cheap ecclesiastical paintings, and the tawdry decorations of the shrines. But in spite of its mutilation and abuse, the Pantheon stands there with an air of conscious dignity, scorning the loss of these external trappings, proud of its past, superior to its present, —a noble in rags, but noble still. Raphael sleeps there, Annibale Carracci, Victor Emmanuel, the late King Humbert, and a score of artists, poets, and statesmen. The martyrs sleep there. They sleep well, and do not see the whitewashed walls. If thought and feeling could ever come back to that sacred dust, there might well come also satisfaction in having for a sepulchre a monument which so closely links the ages, and which has stood so long superior alike to the wrath and to the greed of men. This circular form of building, of which the Pantheon is so perfect an example, was peculiar to the Romans, and appears also, as we have seen, in the mausolea of Augustus and of Hadrian. We shall also see it in the Tomb of Cecilia Metella on the Appian Way, and in the beautiful little Temple of Mater Matuta in the Forum Boarium. For the present, however, we must confine ourselves to the buildings of the Campus Martius. Behind the Pantheon are certain ruins, supposed to have belonged to the Baths of Agrippa. A large vaulted hall is shown, probably the frigidarium, containing niches and the remains of a beautiful frieze. Fragments of ruin are also to be seen on the Via dell' Arco della Ciambella, but the whole plan of the baths is as yet so conjectural, and the ruins so far concealed by modern houses, that in this cursory ramble it is hardly worth while to investigate them. The same is true of certain fragments of ancient masonry in a neighbour ing alley behind the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, belonging probably to the Temple of Minerva Campensis, over which the modern church was erected, and from which it takes its name.

ROME By Walter Taylor Field

Rotunda Square

After the devastations of Rome, this square was buried under the ruins of various ancient edifices, until Eugene IV. freed it. The two lions of Basaltes, now at the fountain of Termini, were then found near the portico of the pantheon. The superb porphyry urn, now in the Corsini chapel at St. John Laterano, was also found there; likewise a bronze head of M. Agrippa, a horse's foot, and a piece of wheel, all in bronze. The fountain in the middle of this square was afterwards made under Gregory XIII., by Honorius Lunghi; Clement XI. placed on it the obelisk, before situated near the church of St. Ignatius, in the Piazza S. Macuto, where Paul V. had erected it. This little obelisk is of Egyptian granite, covered with hieroglyphics : it was found in laying the foundation of the convent annexed to the church of Minerva; it had been placed before the temple of Isis and Serapis, near Minerva's.

A new Picture of Rome, and its Environs, in the form of an Itinerary - Mariano Vasi - 1819